E-book evaluate

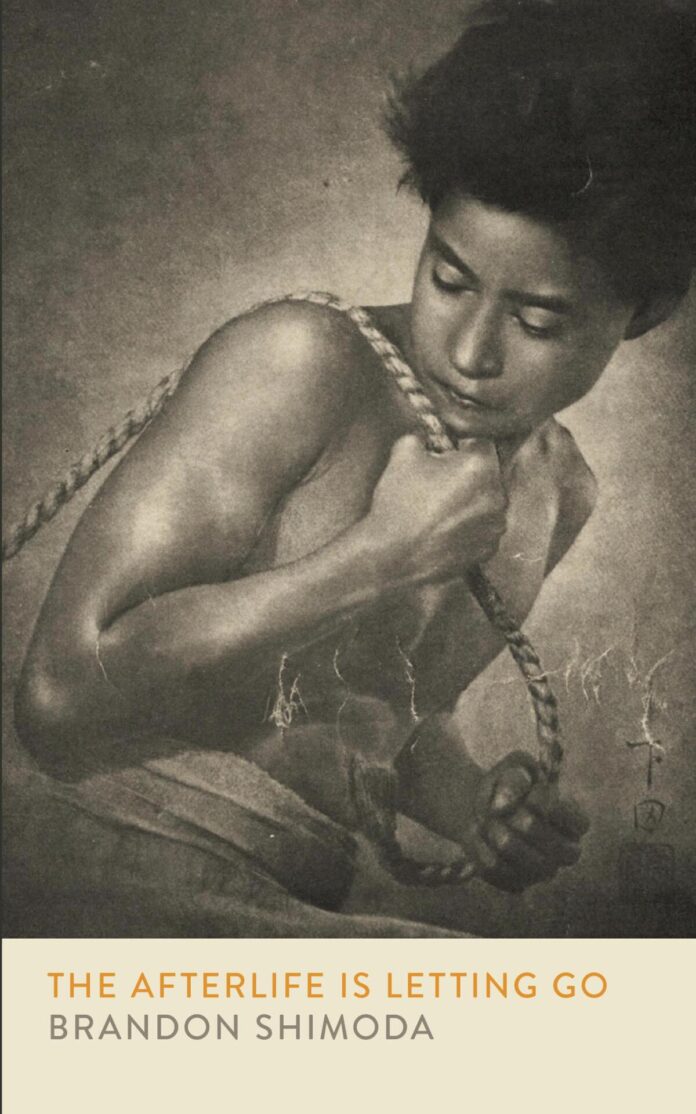

The Afterlife Is Letting Go

By Brandon Shimoda

Metropolis Lights Books: 232 pages, $17.95

Should you purchase books linked on our website, The Instances could earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist impartial bookstores.

Throughout World Battle II, Fred Korematsu, one of many 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese Individuals incarcerated beneath President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Govt Order 9066, refused to be moved into horse stalls and was convicted for resisting. The American Civil Liberties Union challenged his conviction, however the Supreme Court docket dominated towards him, citing army necessity. Forty years on, nevertheless, a federal district courtroom vacated the conviction, as a result of the Division of Justice had initially withheld proof displaying there was no army necessity. Korematsu obtained a Presidential Medal of Freedom. Reparations have been paid to him and others of Japanese ancestry. However the legacy of these imprisonments is pivotal for a lot of Japanese Individuals. Fourth-generation Japanese American poet Brandon Shimoda’s “The Afterlife Is Letting Go,” a well-researched, intriguing essay assortment, reappraises not solely the official narratives but in addition the supposedly ameliorative efforts made subsequently.

In 15 essays, Shimoda blends interviews and private insights, many gleaned from his visits to focus camps across the West. Initially at the least, the multiplicity of voices introduced lend the guide an nearly Lyotardian consciousness that no metanarrative can conclusively embody what occurred. Shimoda’s astounding prologue, “Paper Flowers,” frames the guide’s issues with the picture of a Japanese man, James Hasuaki Wakasa, within the desert bending to select an uncommon flower. However what appears to be an exquisite picture transforms into considered one of brutal governmental violence: We study the person was within the Topaz focus camp and shot by a white teenage guard whose account, Shimoda skillfully demonstrates, was not credible.

In the identical camp, two Issei males erected a 2,000-pound stone monument to Wakasa, however the authorities demanded the monument’s destruction. As a substitute, the 2 males buried the stone, making a covert memorial website. Years afterward, when it was dug up, survivors and descendants of Topaz, together with archaeologists and Topaz Museum members, agreed to depart it in place. One archaeologist defined, “Excavation and removing are by their nature irreversible and damaging acts.” Nonetheless, in 2021, the museum, based by a white English trainer, relocated the stone with out notifying the Japanese American neighborhood. Shimoda writes: “I had a idea earlier than visiting the Topaz Museum: that it’s not for Japanese Individuals, however about them. And that it may not even be about them.”

The time period “internment camp” was lengthy utilized in official paperwork to reduce Japanese Individuals’ ache. Think about the bulk’s assertion in U.S. vs. Korematsu: “We deem it unjustifiable to name them focus camps, with all of the ugly connotations that time period implies — we’re dealing particularly with nothing however an exclusion order.” It’s thus important that “The Afterlife Is Letting Go” is constructed round what essential race idea would name the “counter tales” of Japanese Individuals.

The guide’s model is something however dogmatic — it shares an aesthetic with Shimoda’s poetry, which typically marries summary concepts with seemingly unrelated concrete impressions. In a single essay, when Shimoda reads an Issei couple’s letters whereas sitting within the barracks of Ft. Missoula, Mont., he finds it troublesome to reconcile his grandfather’s imprisonment with the barracks’ “charming, willowy air.” And in “The Wood Constructing Will Be Left for Revenge,” a person on Angel Island, Calif., whispers “researching the ancestors” to him, and Shimoda is uncertain whether or not that is meant to be a query. Later, he repeats the phrases so continuously, he writes: “They grew to become phenomenal, till I used to be now not certain if the person stated ‘researching’ or if what he had really stated was ‘rehearsing.’ As a result of they have been doing that, too.”

A grand narrative of kinds does emerge, because the guide comes into dialog with different anticolonial works resembling Deborah Miranda’s “Unhealthy Indians,” Viet Thanh Nguyen’s “Nothing Ever Dies,” Layli Lengthy Soldier’s “Whereas.” In sure experimental items, Shimoda stacks others’ counterstories with out exposition, privileging the composite group perspective over his particular person take. “Researching the Ancestors” and “Rehearsing the Ancestors” are two such compilations. The previous consists of quoted responses to: “What’s an ancestor? What’s your relationship with them?” Fellow poet Mia Malhotra writes, “Somebody whose vitality I really feel move by me,” and Shimoda’s younger daughter solutions, “A useless particular person you like.”

In “To Pressure Upon Them the Authority of Historical past,” the creator amasses quotes about how incarceration has been taught. A person recounts presenting his mannequin of the Topaz Artwork Faculty: “Out of the blue my class of just about all white college students would flip slowly to have a look at me like I used to be a statue in a museum.” A girl mentions her mannequin of the Tanforan horse stall the place her grandmother was incarcerated. She obtained a C-plus as a result of, she explains: “The venture was alleged to be about genocide. However the incarceration was not murder-y sufficient.” Shimoda’s equalizing of quite a few remembrances produces an indictment of white supremacy by the use of easy accumulation: The anecdotes are comparable sufficient, voluminous sufficient, {that a} reader should conclude the racism was systemic.

Whereas this technique produces a resonance, Shimoda’s experiment can, perversely, hold unhappy experiences emotionally flat for the reader. The depth of his personal descriptions and insights highlights this; for example, after interviewing his grandmother, not incarcerated as a result of she lived outdoors the exclusion zone, Shimoda notes, “I felt seedless and pale, the diminishment of being Japanese in favor of being American.” However in “Japanese American Incarceration for Kids,” he surprisingly units forth the paradox of accumulation: “The historical past has skilled a strained pissed off life. The extra it’s advised, the much less the general public appears to recollect, so when it’s advised — most continuously provoked, today, by current injustice — it begins with a reiteration of the info. It’s much less about info although, and extra about having to begin, with every telling, another time, to appease a citizenry that’s not listening, that’s outlined by its refusal to pay attention.” With these observations, Shimoda requires readers to contemplate that the flattening he has artistically reproduced can also be the sensation of unheard Japanese Individuals.

The Korematsu majority opinion was by no means expressly overturned. In 1983, addressing Choose Marilyn Corridor Patel, who vacated the decrease courtroom’s conviction, Korematsu stated, “We are able to always remember this incident so long as we stay.” As if yielding to that exhortation, “The Afterlife Is Letting Go” turns into a textual monument for present-day circumstances. It acknowledges {that a} literature of and for the folks, not authorities paperwork, could also be a balm for the obfuscations of energy, reminiscence and time.

Anita Felicelli served on the board of the Nationwide E-book Critics Circle from 2021 to 2024 and is the creator of a number of books together with “How We Know Our Time Vacationers: Tales.”