Guide overview

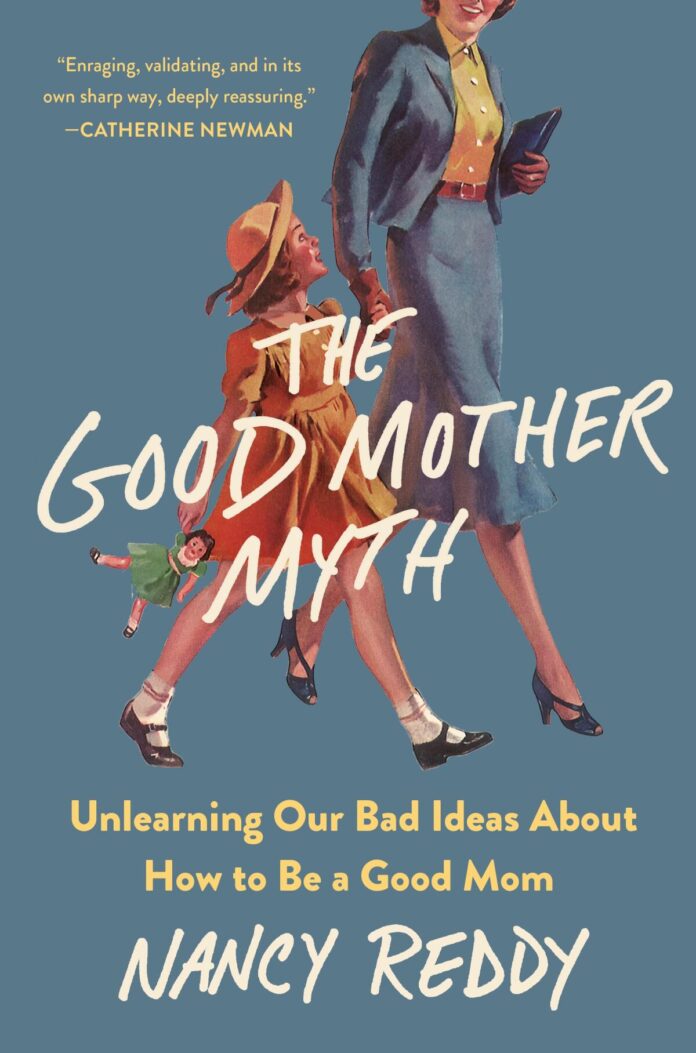

The Good Mom Fable: Unlearning Our Unhealthy Concepts about The way to Be a Good Mother

By Nancy Reddy

St. Martin’s Press: 256 pages, $28

If you happen to purchase books linked on our web site, The Instances might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist impartial bookstores.

In “The Good Mom Fable: Unlearning Our Unhealthy Concepts About The way to Be a Good Mother,” Nancy Reddy juxtaposes her personal uncooked story of early motherhood with a tour of twentieth century parenting science’s biggest hits — or worst failures, relying the way you take a look at it.

“Earlier than I had a child, I used to be good at issues,” Reddy writes in her introduction, beguilingly known as “Love Is a Wondrous State,” a line she nabs from psychologist Harry Harlow. Harlow was one of many first students to check the “science” of motherhood within the lab. That Reddy pokes holes in Harlow’s legacy whereas pursuing a PhD on the College of Wisconsin, the place Harlow carried out his analysis, is among the many e-book’s participating ironies.

Harlow’s most famed experiment positioned toddler rhesus monkeys alongside wire cylinders alternately wrapped in warmed terry material or barbed wire. The infants clung with out fail to the “material mom,” “proving” to Harlow that the best mom was “mushy, heat, and tender… with infinite endurance.” Reddy had imagined herself as a material mom, like “All the great moms who surrounded me in Madison,” however her new son “howled,” “roared,” “kicked,” and flailed,” his cries “an emergency inside my total physique.” Sleepless and gripped by an identification disaster, Reddy spends her days studying Harlow’s papers: “If Harlow had found what made a mom good…on the identical campus the place I studied, I needed to be taught it, too.” What she learns as a substitute is the ability of tradition to bend science to its will.

Harlow pushed what was on the time a radical stance: that breastfeeding wasn’t required for bonding. This prompted one up to date journalist to remark that “anybody could be a mom” — presumably, even a father.

Unsurprisingly, this message by no means made it to the postwar American public, at the same time as Harlow (and John Bowlby, his someday collaborator and the originator of “attachment principle”) had their findings coated by extensively learn magazines. The media largely highlighted the conclusion that moms wanted to be mushy and always accessible.

The scientists, too, appeared to distort the social implications of their work. In a World Well being Group-commissioned report on the state of moms and youngsters within the postwar period, after state-sponsored day care enabled girls to enter the workforce in droves, Bowlby listed “working mom” on a listing of main risks to youngsters, sandwiched between “famine” and “bombs.”

Because the ’50s repackaged Harlow’s findings, the marketing campaign to maintain moms out of the workforce redesigned the lab. Reddy compares psychologists’ experimental setup that “crammed cages with mom rats… every mom remoted together with her offspring” — an try “to check motherhood in its essence” — with the world of “the best suburban housewife, residence alone together with her young children.” Bowlby and Harlow “checked out animals that suited them, they usually noticed what they’d anticipated to seek out” — that the unattainable ultimate of motherhood meant girls doing all of it on our personal, on a regular basis.

Reddy goals to shine a light-weight on how social science fed moms the “false selection” between being all the pieces to our infants or having different ambitions — for work, mates, something outdoors home life. And she or he desires to commerce that mentality for a imaginative and prescient to “share the work,” a model of what cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead known as “alloparenting.”

That’s what the biologist Jeanne Altmann discovered finding out baboons within the wild. The baboon moms, by way of social hierarchy and grooming, fashioned networks of feminine friendships to “defend their offspring from hazard and determine meals sources to share.” Reflecting on an idyllic time in her childhood, Reddy describes how her newly divorced mom and newly divorced aunt shared home areas and little one care, their 4 daughters thriving of their rickety previous homes, watching “The Cosby Present” and doing homework collectively. Till, that’s, each girls remarried and moved their daughters in with their new husbands. “We’d been baboons,” Reddy writes, with rueful tenderness. “Then, we had been rats once more.”

“The Good Mom Fable” is full of memorable one-liners like this (“Some males actually will invent a complete educational self-discipline as a substitute of going to remedy,” Reddy writes drolly of Bowlby). However what saves the writer from being too intelligent or glib is her rigor in analyzing how usually educational scholarship on motherhood relied on socially motivated foregone conclusions, pushed by males who usually uncared for their very own households.

Reddy’s journey can also be private: Her advocacy for a collaborative motherhood is knowledgeable by her horrible loneliness, so frequent in America, in her first yr as a mother. She captures how the occasional visits she will get from family and friends intensify her total isolation, and the way a girl at a postpartum train class sees her when she seems like a drowning, invisible failure.

Just like the legendary good moms she seeks to deconstruct, Reddy is white, straight and prosperous, elevating her youngsters in a two-parent family. Conspicuously absent from the e-book are the difficulties of moms who don’t occupy the identical social place, and the roles that race and sophistication play.

However the concentrate on well-to-do white folks helps make Reddy’s level. Every thing Reddy experiences, from the second she unlatches her nursing bra to reveal her “uncooked and cracked” nipples to her child’s physique contorted with unexplained screams, is an extraordinary a part of what within the U.S. counts as a fascinating parenting scenario. When Reddy tells us that she “was a bleeding, leaking mammal, weeping within the produce part” who barely survived, she’s articulating the expertise of numerous girls throughout the spectrum of American motherhood. She attributes her survival to her capability to ask for, and obtain, assist from the neighborhood of girls she had gathered round her, with a historical past of at all times having her primary wants — respectable healthcare, meals and housing — met. In the event that they hadn’t been — properly, what might need occurred then?

That query reverberates when, one summer time day, Reddy’s sister calls to inform her {that a} girl they knew rising up took her life in a state of postpartum psychosis. “I do know you’ve been having a tough time,” Reddy’s sister says, crying. Reddy assures her that whereas it’s exhausting, it isn’t “like that” — she is “okay,” or OK sufficient. The opposite girl, not OK, turns into Reddy’s shadow because the e-book propels us by way of her son’s first yr of studying to roll over, pull himself up, stroll and speak. Reddy’s emotions of invisibility are made all of the extra actual by her doppelganger’s definitive absence.

Generally I needed “The Good Mom Fable” had been a conventional memoir, as a result of the private sections are so compelling. However the narrative juxtaposition with intensive analysis serves a goal. By rooting the unattainable requirements that taunted her in final century’s bunk science, Reddy takes goal on the underlying energy constructions, together with larger schooling and white supremacy. “The Good Mom Fable” ends with the pandemic; because the partitions shut in on Reddy, she writes, “I lastly cracked.” A variety of us did. She resolves this by insisting that her husband share the load, a transition that she says occurs — after years.

I consider Reddy, and I love her admonition that “a person who genuinely can’t, or received’t, be taught to pack a lunch … will not be a person you must keep married to.” Her e-book makes clear how a lot work we’ve left to do to untangle notions of goodness and prescribed labor from motherhood.

Emily Van Duyne is an affiliate professor of writing at Stockton College and the writer of “Loving Sylvia Plath: A Reclamation.”